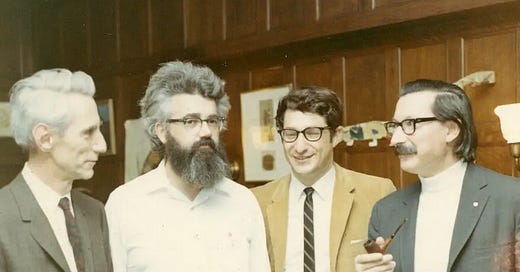

Pamela McCorduck’s Machines Who Think, published in 1979, is a fascinating historical document, capturing the state of AI right before the “AI winter” of the 1980s. The book is steeped in the symbol processing, or the Good Old-Fashioned (GOFAI), paradigm, which is not surprising given both the time when it came out and the author’s unprecedented access to all the key thinkers and researchers who are now indelibly associated with GOFAI: Herbert Simon, Allen Newell, Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy. Many of the ideas, such as Simon’s and Minsky’s dismissal of learning, look rather quaint now. Along with the history of ideas, McCorduck’s book exposes the human element and the human folly. For example, it is amusing to read about Simon, Newell, and others expressing their frustration with Hubert Dreyfus’ philosophical critique of AI and how his message had gotten amplified because of the RAND Corporation cachet attached to his 1965 memo on “Alchemy and artificial intelligence”—in Allen Newell’s words, “the kind of platform” Dreyfus was given endowed him with “an authority and credibility he’s simply not entitled to.” Or the petty dig at Joseph Weizenbaum, the creator of ELIZA who would later become one of the more uncompromising critics of AI, to the effect that the main reason he became a critic is because he was spent as a researcher.

But the more interesting bits are at the end, where McCorduck is interviewing Ed Fredkin, a pioneer in both AI and reversible computing who died earlier this year. I will now quote some of these passages in full—not because I necessarily agree with what he says, but because he prefigured many of the ideas and concerns we are now hearing from people like Geoff Hinton, but with more nuance and more cautious optimism. And, again, keep in mind that Fredkin was saying these things in the 1970s!

On AI as the next step in evolution:

Artificial intelligence is the next step in evolution, but it’s a different step [Fredkin says]. And it’s very different, because the genetic-message concept has disappeared with it. One artificially intelligent device can tell another not only everything it knows in the sense that a human teacher can tell a student some of what he knows, but it can tell another device everything about its own design, its makeup—its genetic characteristics, as it were—and about the characteristics of every other such creature that ever was.

On the gap between humans and advanced AI:

Say there are two artificial intelligences, each about the size of a small table. When these machines want to talk to each other, my guess is they’ll get right next to each other so they can have very wide-band communication. You might recognize them as Sam and George, and you’ll walk up and knock on Sam and say, “Hi, Sam. What are you talking about?” What Sam will undoubtedly answer is, “Things in general,” because there’ll be no way for him to tell you. From the first knock until you finish the “t” in about, Sam probably will have said to George more utterances than have been uttered by all the people who have ever lived in all of their lives. I suspect there will be very little communication between machines and humans, because unless the machines condescend to talk to us about something that interests us, we’ll have no communication.

For example, when we train the chimpanzee to use sign language so that he can speak, we discover that he’s interested in talking about bananas and food and being tickled and so on. But if you want to talk to him about global disarmament, the chimp isn’t interested and there’s no way to get him interested. Well, we’ll stand in the same relationship to a super artificial intelligence. They won’t have much effect on us because we won’t be able to talk to each other. If they like the planet and don’t want to leave, and they don’t want it blown up, they might find it necessary to take our toys away from us, such as our weapons.

On the danger coming from “semi-intelligent” machines:

That problem occurs when we have semiintelligent programs. That is, we have experts who are very advanced in given fields, like DENDRAL in chemistry or MYCIN in internal medical diagnosis, only these are, let’s say, foreign policy experts. But such a machine might be full of bugs. Such a limited expert could bring about catas- trophes we aren’t even able to cause ourselves—ones we aren’t smart enough to concoct. This danger is a temporary one, existing only when the machines are somewhat, but not very, intelligent. For the really intelligent ones will be able to understand our motives, what we want; will be able to look at themselves and understand their own operations, and know that they’re working towards solving the problems we want solved. Whereas the semiintelligent ones will have no such introspection, and will operate in ways that have nothing to do with our highest-level goals.

The last sentence of the above quote alludes to the problem of “alignment.” He elaborates further on the importance of this:

There are ways to arrange that, at least in the interim stage. Eventually, no matter what we do there’ll be artificial intelligences with independent goals. I’m pretty much convinced of that. There may be a way to postpone it. There may even be a way to avoid it, I don’t know. But it’s very hard to have a machine that’s a million times smarter than you as your slave.

Here is Fredkin on the impossibility of the “OFF switch” and on the futility of an “AI pause:”

Look, we see our knowledge of artificial intelligence is slowly growing. Meanwhile, the cost is a handicap that’s about to disappear, first for the laboratories and then for everyone. What’s equally frightening is that the world has developed means for destroying itself in a lot of different ways, global ways. There could be a thermonuclear war or a new kind of biological hazard or what-have-you. That we’ll come through all this is possible but not probable unless a lot of people are consciously trying to avoid the disaster. McCarthy’s solution of asking an artificial intelligence what we should do presumes the good guys have it first. But the good guys might not. And pulling the plug is no way out. A machine that smart could act in ways that would guarantee that the plug doesn’t get pulled under any circumstances, regardless of its real motives—if it has any. I mean, it could toss us a few tidbits, like the cure for this and that.

I think there are ways to minimize all this, but the one thing we can’t do is to say well, let’s not work on it. Because someone, somewhere, will. The Russians certainly will—they’re working on it like crazy, and it’s not that they’re evil, it’s just that they also see that the guy who first develops a machine that can influence the world in a big way may be some mad scientist living in the mountains of Ecua- dor. And the only way we’d find out about some mad scientist doing artificial intelligence in the mountains of Ecuador is through another artificial intelligence doing the detection. Society as a whole must have the means to protect itself against such problems, and the means are the very same things we’re protecting ourselves against.

(Substitute “the Chinese” for “the Russians,” and this would be indistinguishable from many of the writings we see today.)

Here is Fredkin’s tempered optimism:

People are in anguish today, even in primitive societies; they’re in anguish because of the emotional burdens they have to bear. Things can be helped by creating a society that poses fewer such problems, and by helping people to be able to deal with the problems. The point is that artificial intelligence can help to run society in ways that are more beneficial for everyone.

Humans are okay. I’m glad to be one. I like them in general, but they’re only human. It’s nothing to complain about. Humans aren’t the best ditch diggers in the world, machines are. And humans can’t lift as much as a crane. They can’t fly at all without an airplane. And they can’t carry as much as a truck. It doesn’t make me feel bad. There were people whose thing in life was completely physical— John Henry and the steam hammer. Now we’re up against the intellectual steam hammer. The intellectual doesn’t like the idea of this machine doing it better than he does, but it’s no different from the guy who was surpassed physically. So the intellectuals are threatened, but they needn’t be—we should only worry about what we can do ourselves. The mere idea that we have to be the best in the universe is kind of far-fetched. We certainly aren’t physically.

The fact is, I think we’ll be enormously happier once our niche has limits to it. We won’t have to worry about carrying the burden of the universe on our shoulders as we do today. We can enjoy life as human beings without worrying about it. And I think that will be a great thing.

And here is, possibly, the first use of the term “superintelligence:”

There are three events of equal importance, if you like. Event one is the creation of the universe. It’s a fairly important event. Event two is the appearance of life. Life is a kind of organizing principle which one might argue against if one didn’t understand enough—shouldn’t or couldn’t happen on thermodynamic grounds, or some such. And, third, there’s the appearance of artificial intelligence. It’s the question which deals with all questions. In the abstract, nothing can be compared to it. One wonders why God didn’t do it. Or, it’s a very godlike thing to create a superintelligence, much smarter than we are. It’s the abstraction of the physical universe, and this is the ultimate in that direction. If there are any questions to be answered, this is how they’ll be answered. There can’t be anything of more consequence to happen on this planet.

This passage sounds, perhaps, a bit too hopeful and optimistic, but who knows?

I don’t expect Utopia. If we got rid of wars, and weapons of mass destruction, and famine, it wouldn’t change our lives at all, hardly, except to take away certain long-range worries. That’s not Utopia, but it’s a change. All humans are equally precious, and somehow the place can be better managed for them, but not by us. We might become capable of it, but it’s a fantastic burden and a lot of the circumstances, like natural disasters, famines, and so forth, are out of human hands. But what could happen is that the vast majority of people can live happier, better lives, provided we manage our planet well. And AI can help manage the planet well. I’m convinced of it.

Being brought back here from your twitter. Fredkin may have been the first to use "superintelligence," but IJ Good used the same weird rhetoric and the term "ultraintelligence" in 1966.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065245808604180

Very interesting, I did not know about this book. Planning to read it when I get time.